Outlaw APT group – From initial access to crypto mining

Foreword

Eviden Digital Security regularly performs incident response and gathers information on various groups of attackers. In the summer 2022, a company discovered one of their machines was performing SSH brute-force attempts and scanning ports on external targets.

The company contacted Eviden Digital Security to manage the crisis and remediate the incident. Eviden Incident Response Team gathered information about malicious activities on the victim’s machine, which revealed one of the company’s servers had been used to mine Monero with the XMRig cryptominer.

Eviden Incident Response Team attributed the attacks to the Outlaw threat actor with a high level of confidence. Attribution was performed by linking information from Eviden public and private sources to the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) as well as to the Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) observed on the machine.

This article describes the results of the investigations conducted on this group, its modus operandi and attacks campaigns.

Threat overview

The Outlaw threat group is a cryptocurrency mining threat actor that has first been discovered by TrendMicro Researchers in November 2018 [1]. The group is believed to originate in Romania, based on the language, tools and infrastructure it uses [2] [3].

At the time, the group distributed an Internet Relay Chat (IRC) bot, built with the help of Perl Shellbot, available publicly, through the exploitation of a common command injection vulnerability on Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices and Linux servers [4].

One way this campaign was monetized was through the distribution of XMRig, a popular Monero cryptocurrency mining tool used by several other threat actors such as Kinsing or 8220 [5] [6]. TrendMicro estimates that, at that time, the group had compromised close to 200,000 hosts across the world [7].

XMRig miner Website – Source: XMRig [8]

XMRig miner Website – Source: XMRig [8]

Since 2018, Outlaw conducted several infection campaigns and regularly brought modifications to its toolkit and modus operandi. The most recent observation of Outlaw infection attempts dates back to February 2022, as described by CYE researchers [9].

According to TrendMicro, Outlaw is one of the less sophisticated cryptomining threat group as it tends to attack less secure platforms, such as IoT. Consequently, the threat actor mostly reuses the same Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) from one campaign to another [6].

As is the case for most cryptomining threat groups, Outlaw’s objective is inherently financial. Its main aim is to create a botnet and to spread mining activities on a large number of victims and generate money over a long period of time. The botnet would also allow Outlaw to create additional revenue streams by offering DDoS-for-hire services or by selling the stolen information from the targeted servers [10] [11].

It is worth noting that the tools used by Outlaw have also been used in infection campaigns from other cryptomining threat actors, as highlighted by Bitdefender researchers in July 2021 in a research shedding light on another cryptomining threat group likely based in Romania [12].

CRYPTOMINING MALWARE

Cryptomining malware, also called cryptojacking malware or cryptominers, are a relatively recent threat that can target any type of devices, such as personal or office computers, IoT devices, smartphones or cloud servers.

Although recent, cryptominers are already a very common malware category with a continuously growing number of malware variants and victims, as it is seen as less risky when compared to ransomware operations [13].

This category of malware exploits the confirmation process for cryptocurrencies transactions, which is based on the involvement of third-party participants called miners. The latter receive rewards in the form of cryptocurrency coins if they are the first to prove the legitimacy of the transaction by resolving complex math equations [14].

Cryptomining threat groups such as Outlaw thus aim to improve their computing power by leveraging the victim machines’ computing power to mine cryptocurrencies faster, without the associated energy costs.

To this end, most cryptominers are designed to be stealthy and often come with persistence mechanisms and evasion techniques, for instance by only using small amount of computing power per infected machine [15].

The impacts of cryptominers is not limited to a loss of computing power as it can impair the server or device performance, increase electricity cost and reduce your machines’ lifespan. Although generally seen as innocuous, cryptomining malware can significatively damage business performance by slowing down online services, which could lead to customer dissatisfaction and loss of revenue.

An infection with a cryptomining malware is also an indication of poor security hygiene that could be exploited by other cybercriminals groups with more damaging effects.

Victimology

Cryptomining threat groups are generally opportunistic attackers that will infect any machine that is not properly secured, regardless of the industry or geolocation [6].

The Outlaw threat actor is specifically known to target less secured targets in unsophisticated attacks. In this respect, it has notably been observed targeting industries known to have limited resources dedicated to security, such as the Education sector [15].

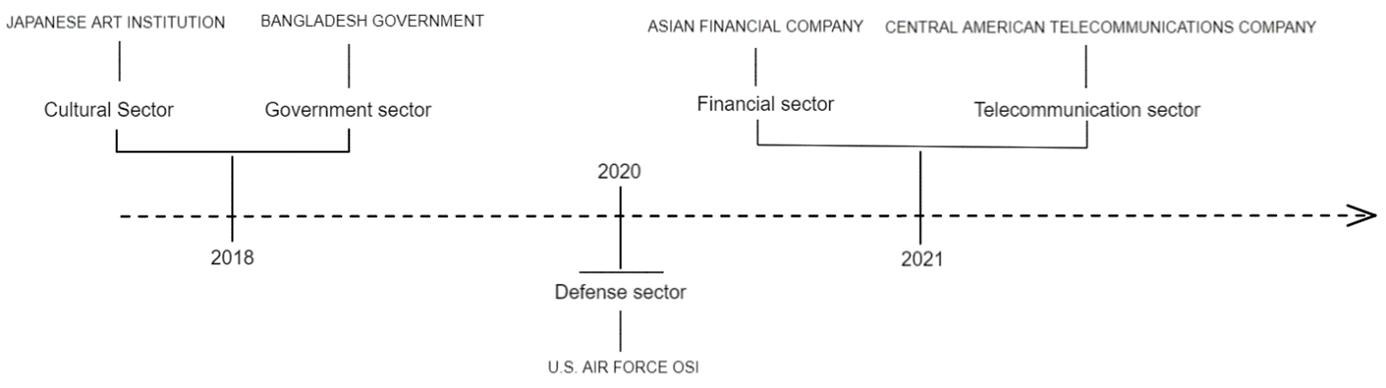

Nevertheless, since its first observation, the group has infected servers in in small of large companies, notably in industries usually more advanced in terms of security, such as the financial or defense industries.

For instance, in May 20221, American military investigators raided the home of a man suspected of having operated the Outlaw botnet to infect a server of the U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (OSI), the Air Force’s internal law enforcement agency [16]. In July 2021, it targeted servers of a Central American telecommunications company and of an unnamed financial company in Asia [17].

Additionally, although the first documented Outlaw infection campaigns targeted Asian entities, the botnet was detected in many countries across all world regions [1]. In 2020, as well as in its most recent 2022 campaign, infection attempts targeted European and American entities [11] [9].

Known Outlaw infected targets

Sources: TrendMicro, The Record, Darktrace [1] [16] [17]

Last Outlaw updates

Outlaw operators have made few changes to their TTPs between 2019 and 2022. This trend is reflected in the IP address associated with their Command&Control server (C2), which has not been modified since their 2021 intrusion campaigns.

However, although minor, some changes have been observed in Outlaw attack campaigns investigated by cybersecurity researchers:

- Yoroi and IBM researchers noted Outlaw uses the XMRig cryptominer in attack campaigns that took place in May 2020 and June 2021. Previously the group used the XMR-STAK cryptominer [18] [19] [20].

- In a December 2020 attack campaign, TrendMicro researchers noted improvements in one of the scripts used by the group, which allows the removal and uninstallation of cryptominers already present on the targeted system, and the removal of previous versions of the malware installed in previous attacks [21]

- In February 2022, Hackernoon cybersecurity researchers observed an Outlaw attack campaign in which the group used the XORDDOS malware, designed to launch large-scale DDoS attacks [9].

Bibliography

[1] TrendMicro, «Perl-Based Shellbot Targets Organizations via C&C» 01 November 2018. Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/18/k/perl-based-shellbot-looks-to-target-organizations-via-cc.html

[2] IBM, «A Fly on Shellbot’s Wall: The Risk of Publicly Available Cryptocurrency Miners» 29 June 2021.

Available: https://securityintelligence.com/posts/shellbot-publicly-available-cryptocurrency-miner/

[3] Yoroi, «Outlaw is Back, a New Crypto-Botnet Targets European Organizations» 28 April 2020. Available: https://yoroi.company/research/outlaw-is-back-a-new-crypto-botnet-targets-european-organizations/

[4] GitHub, «Shellbot.pl.txt» 18 May 2014.

Available: https://github.com/tennc/webshell/blob/master/xakep-shells/PERL/shellbot.pl.txt

[5] GitHub, «XMRig» October 2022.

Available: https://github.com/xmrig

[6] TrendMicro, «A Floating Battleground – Navigating the Landscape of Cloud-Based Cryptocurrency Mining» 30 March 2022.

Available: https://documents.trendmicro.com/assets/white_papers/wp-navigating-the-landscape-of-cloud-based-cryptocurrency-mining.pdf

[7] TrendMicro, «Outlaw Group Distributes Cryptocurrency-mining Botnet» 19 November 2018. Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/18/k/outlaw-group-distributes-botnet-for-cryptocurrency-mining-scanning-and-brute-force.html

[8] XMRig, «XMRig» Available: https://xmrig.com/

[9] Hackernoon, «Outlaw Hacking Group Resurfaces» 31 May 2022.

Available: https://hackernoon.com/outlaw-hacking-group-resurfaces

[10] Cybernews, «Outlaw hackers are back – and they’re tougher than ever» 24 February 2022. Available: https://cybernews.com/security/outlaw-hackers-are-back-and-theyre-tougher-than-ever/

[11] TrendMicro, «Outlaw Updates: Kill Old Miner Versions, Target More,» 10 February 2020 Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/20/b/outlaw-updates-kit-to-kill-older-miner-versions-targets-more-systems.html

[12] Bitdefender, «How We Tracked a Threat Group Running an Active Cryptojacking Campaign» 14 July 2021.

Available: https://www.bitdefender.com/blog/labs/how-we-tracked-a-threat-group-running-an-active-cryptojacking-campaign

[13] Kaspersky, «The state of cryptokacking in the first three quarters of 2022» 22 November 2022.

Available: https://securelist.com/cryptojacking-report-2022/107898/

[14] MalwareBytes, «Cryptojacking»

Available: https://fr.malwarebytes.com/cryptojacking/

[15] BlackBerry, «Outlaw Monero Cryptokacking in the Wild» 07 May 2019.

Available: https://blogs.blackberry.com/en/2019/05/outlaw-monero-cryptojacking-in-the-wild

[16] The Record, «Agents raid home of Kansas man seeking info on botnet that infected DOD network» 12 May 2021.

Available: https://therecord.media/agents-raid-home-of-kansas-man-seeking-info-on-botnet-that-infected-dod-network/

[17] Darktrace, «Comment l’IA a découvert l’opération secrète d’extraction de crypto-monnaies d’Outlaw» 11 October 2021.

Available: https://fr.darktrace.com/blog/how-ai-uncovered-outlaws-secret-crypto-mining-operation

[18] Blackberry, «Outlaw Monero Cryptojacking in the Wild» July 2019.

Available: https://blogs.blackberry.com/en/2019/05/outlaw-monero-cryptojacking-in-the-wild

[19] Yoroi, «Outlaw is back, a new crypto-botenet targets eurpoean organizations» May 2020. Available: https://yoroi.company/research/outlaw-is-back-a-new-crypto-botnet-targets-european-organizations/

[20] IBM Security, «A Fly on ShellBot’s Wall: The Risk of Publicly Available Cryptocurrency Miners» June 2021.

Available: https://securityintelligence.com/posts/shellbot-publicly-available-cryptocurrency-miner/

[21] Trend Micro, «A Floating Battleground : Navigating the Landscape of cloud-based Cryptocurrency Mining»

Available: https://documents.trendmicro.com/assets/white_papers/wp-navigating-the-landscape-of-cloud-based-cryptocurrency-mining.pdf

[22] Trend Micro, «Outlaw’s Botnet Spreads Miner, Perl-Based Backdoor» June 2019.

Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/19/f/outlaw-hacking-groups-botnet-observed-spreading-miner-perl-based-backdoor.html

[23] Hackernoon by CYE, «’Outlaw Hacking Group’ Resurfaces» May 2022. Available: https://hackernoon.com/outlaw-hacking-group-resurfaces

[24] Trend Micro, «Outlaw Updates: Kill Old Miner Versions, Target More» February 2020. Available: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/20/b/outlaw-updates-kit-to-kill-older-miner-versions-targets-more-systems.html

[25] Darktrace, «how-ai-uncovered-outlaws-secret-crypto-mining-operation» October 2021. Available: https://fr.darktrace.com/blog/how-ai-uncovered-outlaws-secret-crypto-mining-operation